Blog

This is where you’ll find all the latest updates from Restore Our Planet.

Two Beavers Born in Cornwall Mark Conservation Milestone

July 17, 2025

Two baby beavers have been born at the Lost Gardens of Heligan, Cornwall. The event, while seemingly modest, carries profound implications for conservation efforts across Britain. Beavers were once a familiar presence across the nation’s rivers and wetlands, but were hunted to extinction more than four centuries ago for their pelts and perfume extracts.

The parent beavers, named Twiggy and Byrti, were introduced into a captive breeding enclosure on the Heligan estate in 2023 and early 2024. The habitat, crafted in collaboration with the Beaver Trust and Natural England, was intended to give the animals the conditions they need to thrive: slow-moving water, abundant vegetation, and, crucially, peace from human interference. For months, the team watched closely for signs of success, unsure if the animals would adapt. The arrival of the kits confirms what many had hoped: not only have the beavers settled in, they have started a family.

Staff at Heligan have expressed cautious delight. Young beavers are notoriously elusive in their first few weeks. They stay hidden in the lodge, only venturing out when strong enough to swim. It is believed the kits were born earlier this spring making their emergence now a sign of growing confidence and comfort to their surroundings. The team has been monitoring their development from a respectful distance, using trail cameras and signs in the landscape to piece together a picture of how the young family is progressing.

This development is more than just a charming story about woodland creatures. Beavers are considered “ecosystem engineers” for a reason. As we have previously covered, their presence dramatically reshapes the environments they inhabit. As they build dams and dig canals, they create wetlands that support a wide range of life from dragonflies and frogs to bats and birds. Their work also slows water flow, which can reduce downstream flooding and help maintain moisture in the landscape during dry spells.

Cornwall, like many parts of Britain, faces increasing challenges from extreme weather. The natural water management that beavers provide is not a silver bullet, but it is a low-cost, low-impact way of building resilience into the land. Already, farmers and landowners involved in beaver projects elsewhere in the country (where beaver populations are now believed to be between two or three thousand) have reported better water retention, improved soil quality, and a noticeable increase in local biodiversity.

The birth of the kits also hints at a future in which beavers might return to the wider Cornish countryside. While the Heligan enclosure is secure and closely monitored, it is part of a national movement pushing for wild releases. Earlier this year, the government granted licenses for free-living beavers to be released into English waterways for the first time in centuries. Cornwall Wildlife Trust is already preparing for such a step, with plans underway for a wild release in the Par and Fowey catchment later this year.

For now, the young beavers remain close to home. They will likely stay with their parents for a couple of years before setting out to form territories of their own. It is too soon to say where that journey will take them. But their birth marks a turning point, not just for Heligan, but for the broader story of rewilding in Britain.

European BeaverHarald Olson

Mother and kit

Beaver dam

Record-Breaking Butterfly Boom Marks New High for British Rewilding

July 10, 2025

On July 1st, conservations at the acclaimed Knepp Wildland farm, regarded as one of the origins of the current ‘(Re)Wilding’ movement under the dedicated supervision of proprietors Isabella Tree and Charles Burrell, recorded an astonishing 283 purple emperor butterflies in one day. This figure is believed to be the highest ever daily count of the vulnerable yet striking Papilionidae native with its iridescent wings.

The purple emperor, Apatura iris, is a species long cloaked in mystique. Males spend much of their lives high in the tree canopy, descending only to feed on aphid honeydew or animal dung. For much of the 20th century, their numbers dwindled, as has so often been the case due to habitat loss and the destruction of woodland edges and the sallow trees essential for their breeding.

Knepp’s suite of rewilding projects have been steadily rolled out over their 3,500 acres of former arable land over the past decade. The pioneering couple have traded in intensive agriculture for a bold experiment in ecological restoration. Rather than adopting the micromanaging strategies that have characterised conservation for generations, they have chosen to adopt a more radical ‘laissez faire’ philosophy which allows nature to shape the dynamic processes of ecosystems.

The results have been remarkable. Alongside the rise of the purple emperor, Knepp has seen the return of turtle doves, nightingales, and even nesting white storks, species absent from much of the English countryside for generations. Beavers were reintroduced in 2020 and are now reshaping watercourses in ways that benefit wetland flora and fauna alike.

“This is what nature does when you stop trying to control it,” Said Tree, who is also author of the eminent book, Wilding, which tracks their early experiences. “By creating the right conditions, sallow scrub, open rides, undisturbed woodland margins, we’ve given this incredible butterfly the chance to thrive.”

She’s not alone in her enthusiasm. Neil Hulme, a butterfly expert with Sussex Wildlife Trust, has spent years monitoring purple emperor populations. “Knepp has the largest and healthiest population I’ve ever seen,” he said. “To walk among dozens of them on a summer’s day is like stepping into a fairytale.”

The couple’s approach rejects the planting of trees in tight rows or the preserving of set-aside areas. They have also famously introduced free-roaming species such as Tamworth pigs, Exmoor ponies, red and fallow deer. These native herbivores uproot the soil, trample bramble bushes, and create a patchwork of open scrub, meadows, and, with time, regenerated woodland. This habitat variety is exactly what purple emperors, and many other species, need to thrive.

Knepp’s philosophy has been driving projects across the country and influencing landowners and councils across Britain.

The timing could hardly be more crucial. With Britain facing biodiversity decline and struggling to meet climate goals, rewilding offers a practical, hopeful path forward. It bridges conservation and climate resilience by restoring soil, increasing carbon storage, and protecting watersheds, all while bringing back the species that once defined our country.

Of course, rewilding is not without controversy. Some farmers remain sceptical, citing concerns over food production and land use. But the evidence from Knepp is compelling: nature’s recovery is not only possible but it can be rapid, vivid, and work to restore the connection of British people to their native soil.

Male Purple Emperor ButterflyCharles J. Sharp

Underwing of the same male

Purple Emperor CaterpillarHarald Supfle

Heath Fritillary Butterfly Makes a Remarkable Comeback on Exmoor

June 26, 2025

The heath fritillary (Melitaea athalia), one of Britain’s rarest and most threatened butterflies, is making a striking recovery on Exmoor’s Holnicote Estate, with more than 1,000 individuals recorded this spring. This a significant increase from the 600 recorded the previous year.

Once close to national extinction, the butterfly’s revival is the result of focused conservation efforts by the National Trust and Butterfly Conservation, aimed at restoring its preferred habitats through traditional land management techniques.

The heath fritillary depends on warm, open woodland clearings where common cow-wheat, its primary caterpillar food source, grows in abundance. Historically, the species thrived in areas shaped by rotational coppicing and grazing, practices that declined over the past century, causing severe habitat loss and population collapse.

At Holnicote, conservation teams reintroduced Devon red cattle to manage vegetation, cleared encroaching bracken and bramble, and brought back coppicing methods. These efforts have paid off: the butterfly has returned to three previously vacant sites, and numbers at another location rose from just four individuals last year to 186.

“We’ve been working to bring back the landscape the heath fritillary depends on. It’s a brilliant result and shows the value of long-term conservation planning.” Said Chris Luffingham of the National Trust.

The species emerged earlier than usual this year, likely due to a warm and dry spring; a development that may have helped boost the count. However, conservationists are cautious. Sudden cold snaps or prolonged rain during the breeding period could have a major impact.

“This success is encouraging, but there’s still a lot of uncertainty,” said Dr Caroline Bulman of Butterfly Conservation. “The species is incredibly sensitive to changes in the environment. We need to keep managing habitats carefully and monitor how the population responds over time.”

The work on Exmoor is already drawing attention from conservationists working elsewhere. Similar methods of restoring grazed and coppiced woodland with a focus on specialist food plants could support other declining butterfly species and pollinators in fragmented landscapes.

This positive story stands out against a backdrop of wider concern for UK wildlife. Recent studies have warned that more than 500 bird species could vanish globally in the next century due to climate change and habitat loss. In England, water abstraction has reached record levels, and debates continue over a proposed Planning and Infrastructure Bill that some fear could weaken local environmental protections.

In contrast, the heath fritillary’s recovery offers a tangible example of how conservation can work when it’s grounded in local knowledge and carried out over time.

Habitat work at Holnicote will continue throughout the summer, with plans to strengthen habitat links across the region. The hope is to establish a more stable network of sites where the butterfly can thrive, not just in Exmoor, but in other parts of south-west England.

Heath Fritillary ( Melitaea athalia )

Melitaea athalia

Heath Fritillary caterpillar

Atlantic Bluefin Tuna. A Textbook Case in Species Recovery.

June 5, 2025

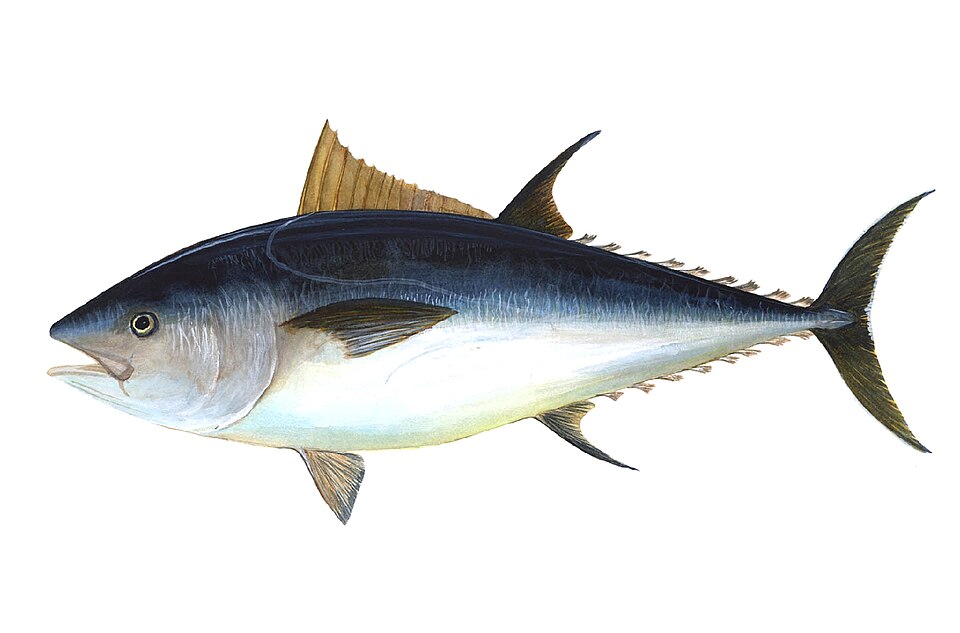

Almost pushed to extinction through overfishing, the Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) is making a remarkable comeback across the oceans of Britain. This return has been a triumph for marine conservationists who have fought hard for implementing sustainable fishing practices and committed ongoing monitoring efforts which are now bearing fruit.

It’s a familiar and troubling pattern across the British Isles: once-abundant species like the Atlantic bluefin tuna thrived for centuries, only to be driven to collapse by the pressures of industrialisation, rapid 19th-century population growth, and the unchecked rise of commercial fishing, particularly in the North Sea and the South West Coast.

By the 1960s tuna had been almost fully extirpated; a sobering loss of not just one species, but of a vital component of marine ecosystems. Recognising the urgency of the situation, the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) began enforcing strict quotas and monitoring in the early 2000s, paired with a moratorium on industrial fishing.

With time passing, sightings have been steadily increasing indicating a bounceback in overall population sizes, most notably in the Celtic and North Seas. Marine conservationists conducted a three-year tagging programme which tracked tuna across their migration routes. The subsequent data revealed their seasonal patterns and brought to light their spawning grounds. This vital data equips scientists and policymakers with the tools they need to implement further management plans to further support the tuna’s recovery.

In 2023, the UK held its first regulated commercial tuna fishing season in over six decades, carefully monitored and limited to a small number of licensed vessels. The season contributed an estimated £2.6 million to local economies, but more importantly, it was seen as a test of whether a commercially viable fishery could coexist with conservation goals. One of the licensed fishers, Angus Campbell from the Isle of Harris, is among those pioneering a model that combines careful harvesting with ecotourism. His boat, Harmony, not only supplies top-quality tuna to local and international markets, including Japan, but also runs catch-and-release experiences, helping to educate visitors about the importance of responsible fishing.

While the bluefin tuna is experiencing a positive trend in population growth, it is important to remain cautious. This highly prized fish, coveted on dinner plates around the world, will always be vulnerable and at risk of overexploitation. Therefore, authorities must maintain efforts for sustained monitoring and enforcement of laws.

Advocacy groups are also calling for stronger international cooperation and for Britain to lead by example in implementing long-term catch-and-release policies, enhanced marine protections, and continued investment in research.

The tentative return of the Atlantic bluefin tuna to British waters is a testament to nature’s persistence and ability to recover if responsibly managed. With ongoing commitment and continued advocacy, collective work has shown that we can begin to mend what has once been lost. An encouraging sign for other lost species severed from our more naturally intuitive past.

Bluefin Tuna ( Thunnus thynnus )

A group swimming.

Atlantic Bluefin Tuna

Are elk the next species to make a return to Britain?

May 9, 2025

Following the overwhelmingly successful return of beavers to the British Isles which has been widely celebrated by the public, efforts are now being organised to bring back another lost species, one that has been absent for over three millennia.

The European elk (Alces alces), the same species as the moose of North America, could be seeing a return following a groundbreaking grant offered by Rewilding Britain to the Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire Wildlife Trusts.

These hefty woodland foragers and wetland grazers are a lost keystone species that can weigh up to 1200 pounds. Their return and proliferation would stand as a measure of restoration for these two long-plighted British habitats where they would serve, similarly to beavers and bison, as ecosystem engineers.

The project aims to reintroduce elk alongside beavers to share habitats, a poignant reuniting of both persecuted species.

“This exciting project could demonstrate how this crucial ecosystem engineer can thrive in floodplain landscapes, shaping diverse habitats that benefit communities and support biodiversity recovery. It may also serve as a catalyst for engaging people in the long-term benefits of returning elk to the wild.” Said Rachel Bennett, Deputy Director of Wilder Landscapes and Derbyshire Wildlife Trust.

The first phase involves housing elk within controlled environments due to legal restraints and their listing under the Dangerous Wild Animals Act of 1976, a piece of legislation that many conservationists argue is outdated as it was passed to serve a widespread popularity for exotic animals in that era. This policy has frustrated many other reintroduction projects for more native and ecosystem-friendly species such as lynx and wild boar.

While the British government currently has no immediate plans for additional wild releases beyond beavers, the success of the elk project could pave the way for future reintroductions of other native species. Public engagement and support will be crucial in shaping the future of Britain’s continued rewilding efforts.

A Male Bull Elk

Cow and calf elk

How to set up your Spring bird box

April 15, 2025

Rich in greenery and technically a forest, England’s capital pulses with more than just the rhythm of traffic, offering residents a unique opportunity to connect with native birdlife.

Crowded high-rises become perches, rooftops offer moments of respite, and pockets of garden serve as quiet havens. With spring arriving atop a week of glorious sunshine, what better time to welcome birds?

Throughout our concrete maze, birds seek out dependable places to feed and rest. So how can we best install bird boxes and truly invite them in?

Finding the right bird box in the perfect spot

In a typical year, over two hundred bird species are recorded across the city. Yet some are far more likely to visit than others, each with their own unique needs.

Blue tits and great tits (small box with a 25–28mm hole)

Robins and wrens (open-fronted boxes in secluded spots)

Sparrows and starlings (larger boxes with 32mm holes)

Feeders and other exposed food sources often draw in larger, territorial birds, like crows or pigeons, who can outcompete and intimidate their smaller counterparts.

Placement is crucial

Position the bird box high enough to stay safe from curious pets and prowling foxes, but not so high that it tempts larger birds. A wall or fence makes an ideal spot, somewhere shaded from harsh sun and shielded from strong winds.

While city birds may be more familiar with the urban bustle than their rural cousins, they still seek out calm, shaded corners with a touch of leafy cover.

As the sun continues to grow in confidence with summer approaching, a bird bath or dish of water would be a welcome refreshment, plus another reason for birds to pay a visit. By providing vegetation or decaying logs, you could create both cover and a thriving insect buffet.

Consider a window box or container garden with pollinator-friendly flowers like lavender, foxglove, or marigolds—these attract insects that birds feed on.

Food

Fat balls (nutrient dense spheres), sunflower seeds, and mealworms.

Avoid cheap seed mixes that might attract pigeons and rats.

Record and share what you see!

Birdwatching helps to build communities. Sharing your sightings with others might encourage them to set up their own or do more for nature where you live. There are a number of popular apps such as Merlin Bird ID and RSPB’s BirdTrack which help with identifying species and contributing to wider understanding of bird population movements and patterns. There are many social media groups encouraging people to come together.

Though it may feel like a small act, with an estimated 70,000 to 100,000 bird boxes across London, you’re joining a vast community. After all, nature belongs to us because we belong to nature, even in the heart of the city!

Bird Box

Swift in a bird box

Migrants Across the Gulf Stream: European Eels

March 27, 2025

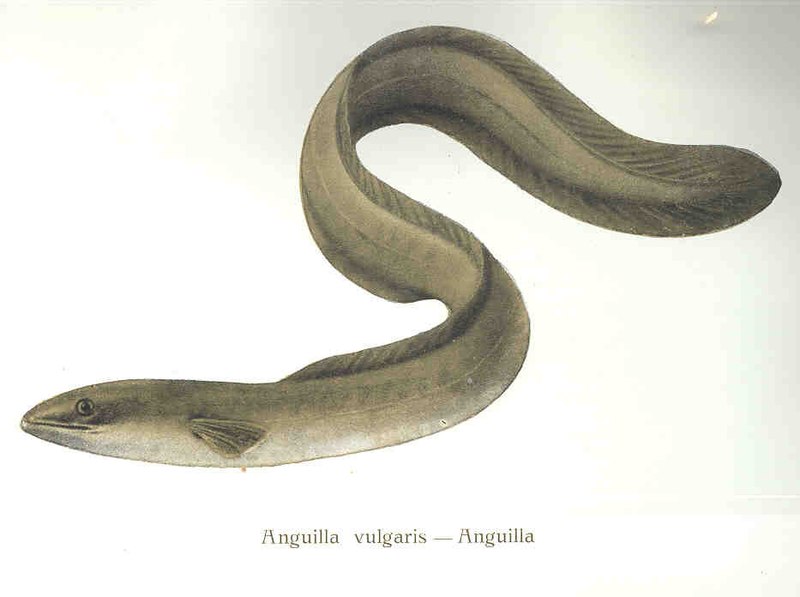

One of the marine world’s greatest migrations from the Caribbean across the Gulf Stream, the European eel (Anguilla anguilla) makes the vast four thousand mile journey twice in its lifecycle.

Born as larvae among the ocean flora of the Sargasso Sea, these Bermudan natives drift across the Gulf Stream to the Mediterranean and Northern Europe, a feat which takes up to two years.

Undergoing metamorphosis from transparent leptocephali to adolescent glass eels, they begin to inhabit river estuaries marking them as one of the few marine species which undergo catadromous migration, inhabiting both the sea and freshwater habitats in their lifetimes.

From here they morph further from elvers, Yellow eels, before taking their final form brilliant Silvers. Over several years they have developed pigmentation, an enlargement in the eyes and a restructuring of the digestive system to suit their newly inhabited freshwaters,

However, with interruptions to the flow of the Gulf Stream due to warming waters brought on by climate change, their journeys have become more difficult. Since only the 1980s, European eels populations have cratered by up to 95%. Not only is this downstream from climate change itself, but the ecological turmoil brought on by wetland drainage, barriers to migration such as dams, overfishing, and a preponderance of pollution and disease.

These woes interfere with one of the most important parts of the eel’s life cycle: its remigration across the swell of the Atlantic back to Sargossa to breed. If they are fortunate enough to make it this far to reproduce they finally perish.

With so many vulnerable species the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has classified the European eel as “Critically Endangered,” highlighting the urgent need for conservationists to take action.

In Britain, organisations like the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust (WWT) are actively involved in restoring wetland habitats, providing crucial environments for eels to thrive.

Efforts to install fish passes and remove obsolete barriers have been implemented to facilitate eel migration, allowing access to upstream habitats essential for their development.

The Canal & River Trust emphasizes the importance of responsible fishing practices, advocating for the return of captured eels to the water to support population recovery.

Controversial measures, such as the export of juvenile eels from the Severn Estuary to Russia, have been undertaken with the intention of providing the eels with access to less degraded habitats, although these actions have sparked debate among conservationists.

Beyond their ecological importance, European eels hold a rich cultural heritage in Britain.

Famously, eels have been a staple in British cuisine for centuries, particularly in the East End of London, where dishes like jellied eels became iconic. This delicacy, made by boiling eels and allowing the broth to set into a jelly, was especially popular among the working class in the 18th and 19th centuries (somewhat less so today).

Eels feature in various British myths and legends. In some folklore, eels were believed to possess mystical qualities, and their elusive nature contributed to tales of them being supernatural creatures.

In Britain, species. Moreover, acknowledging and preserving the cultural heritage associated with eels can foster greater public engagement and support for conservation initiatives. The plight of the European eel serves as a poignant reminder of the broader challenges facing freshwater species worldwide and underscores the need for integrated approaches to biodiversity conservation.efforts to restore habitats, remove migratory barriers, and regulate fishing practices are crucial steps toward ensuring the survival of this enigmatic species.

European Eel

Anguilla vulgaris

Glass Eels. Adolescent Phase

The British Government Approves Beaver Reintroductions in England

March 7, 2025

The landmark ruling has given the go ahead for the iconic and long extirpated native species to make a long overdue comeback. Building upon already growing populations across the country, conservation organisations are celebrating the decision following years of advocacy showing the widespread positive impact beavers have on habitat rejuvenation and climate change mitigation.

“Beavers are unparalleled in their ability to restore landscapes, create wetlands that manage flood risk, improve our water quality, and bring back wildlife.” Said Hilary McGrady, Director General of the National Trust.

The decision follows successful trial projects, such as the River Otter Beaver Trial in Devon, which highlighted vital evidence of the beaver’s ecological benefits. Conservation groups will work closely with local communities to monitor the impact of the reintroduction and provide support where needed.

Beavers are renowned for their ability to transform landscapes. As ecosystem engineers, they build dams that create wetlands, improving water quality and providing vital habitats for fish, birds, and amphibians. Their presence also helps mitigate the impact of extreme weather by naturally regulating water flow, reducing soil erosion, and preventing floods.

“The return of beavers is a significant landmark for nature recovery in England.” Said Tony Juniper, chair of Natural England.

The reintroduction of beavers will be carefully managed to ensure balance between nature and human activity. As their populations grow, conservationists will study their effects on the environment, helping to shape future policies on rewilding and sustainable land management.

Authorities have compiled strict licensing and management legislation to appease the concerns of farmers and landowners against potential agricultural disruptions. Crucially, this type of work is being carried out with the full inclusion of local-community ideas and concerns which has unfortunately not always been the case historically.

Following their demise in the 17th century through widespread hunting for their treasured furs and castoreum, the latter being an ingredient historically used in perfume, the semi-aquatic rodents are set to thrive once more in one of their native domains.

This initiative highlights Britain’s commitment to using nature-based solutions to combat environmental challenges, making the countryside more resilient and ecologically rich for generations to come.

Wilding Profile: Common Crane

February 7, 2025

Common cranes (Grus grus) are tall, long-legged birds with a wingspan of up to 2.4 metres and a height of approximately 1.2 metres. They have predominantly grey plumage, black flight feathers, and a distinctive ruby-red patch on their heads. Like most bird species, they are omnivorous, feeding on a varied diet of plants, insects, amphibians, and small vertebrates. As of 2015, their global population was estimated at between 491,000 and 503,000 individuals, with the majority breeding in Russia, Finland, and Sweden.

One of the most iconic aspects of crane behaviour are their synchronised courtship displays of dance and amorous calling songs. These rituals reinforce pair bonding, as common cranes, like many large, slow-breeding birds, mate for life. This is also typical among many long-lived species where cranes can live up to 40 years of age. They are highly migratory birds, with populations breeding in northern Europe and western Asia before migrating to southern Europe and Africa for the winter.

The common crane was once a common sight in Britain’s wetlands. However, by the early 1600s, the species had almost completely disappeared due to extensive drainage of marshlands for agriculture and relentless hunting, both for food and for use in ceremonial feasts. Owing to their already low populations, they were seen as luxury delicacies and prized particularly during Lent where they were considered ‘fish’ under medieval catholic dietary rules. This view of them as symbols of high status thus plummeted their final numbers into near complete extinction across the British Isles by the 17th century.

Following centuries of absence, in 1979 a small breeding colony was discovered in the wetlands of the Norfolk Broads. As an already declining habitat affecting many other vulnerable species such as the iconic curlew, this inspired conservationists into action. Over the following decades, conservation organisations such as the RSPB, the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust (WWT), and Natural England launched initiatives to help the crane population recover.

One of the most significant projects was the Great Crane Project, launched in 2010. This initiative aimed to boost Britain’s crane population by releasing captive-reared birds into suitable habitats. Using techniques developed in Germany, young cranes were hand-reared at WWT Slimbridge and then released in the Somerset Levels and Moors, a landscape carefully managed to provide ideal breeding conditions. Over several years, dozens of cranes were released, and many successfully established breeding territories.

Today, Britain’s common crane population stands at over 200 individuals, with breeding populations in Norfolk, Suffolk, Cambridgeshire, Somerset, Gloucestershire, and parts of Wales. The success of reintroduction efforts has led to an increase in both the number of breeding pairs and the geographic range of the species. These birds are now successfully raising chicks in areas where they had been absent for centuries.

As previously mentioned, wetland conservation has played a crucial role in the resurgence of and protection of bird species. By restoring traditional wetlands and creating new reserves, conservation groups have provided crucial nesting and feeding grounds. Sites such as the RSPB’s Lakenheath Fen and the WWT’s Welney Wetland Centre have been instrumental in supporting the species’ recovery.

Despite their remarkable comeback, common cranes are still incredibly vulnerable and are faced with the common plethora of modern ecological challenges. Habitat destruction due to agriculture and urban development remains a concern, as cranes require large, undisturbed wetland areas for breeding and feeding.

A lack of general education and awareness also leaves their delicate breeding conditions at risk to even the lightest of human activities of recreation, traffic and noise pollution. These factors often cause long-term breeding failures in a species already suffering from low reproductive rates (largely known as K-breeding strategy).

Species of this slow breeding pattern compensate with high parental investment, dedicating significant time and resources to raising their young. They typically have long lifespans, often living for decades, which allows for multiple breeding opportunities despite their slow reproduction. These species also reach sexual maturity late, taking years before they can reproduce. While their populations remain stable in undisturbed environments, they are particularly vulnerable to habitat loss and overexploitation. Humans are one such species.

The return of the common crane to Britain is a remarkable conservation success story. From complete extinction in the 17th century to a small but tentatively growing population today, the efforts of conservationists, land managers, and the public have made a significant impact.

With ongoing and continued efforts the loving courtship calls of common cranes may once again echo across Britain’s wetlands for generations to come!

Common Crane Adreas Trepte

An adult crane in flight.

A juvenile crane developing adult plumage.

Illegal Lynx releases Spark Ongoing Debate Around Ethic of Rewilding Practices

January 14, 2025

Earlier this month ( January 2025 ) authorities discovered that four Eurasian lynx had been illegally released into the wild near Kingussie in the Scottish Highlands causing controversy and calls for wider questions around the ethics of certain rewilding practices.

The situation has drawn ire from both local communities and conservationists highlighting the complexities of carnivore reintroductions across the British Isles.

Though generally viewed as a non-threat to humans or livestock due to the lynx’s skittish and elusive behaviour, unfortunately these four individuals have been described as “tame and ill-prepared for life in the wild” meaning they were likely to fall prey to the harsh conditions of the highlands and struggle to acquire food. This was further complicated by the fact that one lynx died shortly after capture by authorities, likely due to the stress of the ordeal.

“Any such reintroduction must follow legal protocols, including ecological assessments and public consultations,” emphasised Scottish government representatives. The events have led to a police investigation and calls by conservation groups for those responsible to be charged.

Despite these unfortunate events strong advocacy still remains for the reintroduction of lynx across Britain along with frustration on the overall lack of progress for rewilding a number of extirpated species.

Lynx are believed to have vanished from the British Isles around a millenia ago due to persecution, hunting and the destruction of woodland habitats. However, they play a central role in controlling herbivore populations, particularly deer, which are currently vastly overpopulated and having devastating effects on forest growth and biodiversity. “Bringing back lynx could allow our forests to flourish again,” stated the Lynx UK Trust.

The Eurasian lynx is the largest of Europe’s wild cats, known for its tufted ears and short tail. Typically weighing between 18 to 30 kilograms, they are solitary and territorial, inhabiting dense forests where they prey on deer, hares, and other small mammals.

The challenges of reintroducing lynx remain significant. “We’re dealing with a landscape that has changed dramatically since lynx last roamed here,” said a National Trust spokesman. Human settlements, agricultural activity, and the potential impact on livestock are key concerns for local communities who feel they have been ignored in the conversation.

The illegal release has also highlighted the importance of adhering to legal procedures in rewilding projects. Conservation bodies stress that any reintroduction must be carefully planned, with robust scientific evidence, legal approvals, and community support. Public consultations are a critical component, ensuring that locals are fully engaged in the decision-making process.

Rewilding advocates emphasise the need for broad public support to make such initiatives successful. Recent surveys indicate growing public interest in rewilding, with many viewing it as a means to address the twin crises of biodiversity loss and climate change. However, some remain skeptical, citing potential conflicts between conservation goals and agricultural practices.

Organisations like the Lynx UK Trust have been conducting consultations and education campaigns to foster understanding and support for their proposals. “It’s not just about bringing back lynx,” a representative explained. “It’s about restoring ecosystems and creating a future where humans and wildlife coexist.”

Across Europe, successful lynx reintroduction programs offer valuable lessons for Britain. Countries such as Germany, Switzerland, and Slovenia have seen lynx populations thrive when reintroduced through well-regulated programs. These initiatives often involve habitat restoration, long-term monitoring, and compensation schemes for farmers whose livestock are affected by predation.

Despite these successes, challenges remain. Human-wildlife conflicts, habitat fragmentation, and illegal hunting pose ongoing threats to lynx populations. Britain must learn from these experiences to ensure any future reintroduction avoids similar pitfalls.

Stalking lynx Tony Hisgett

Lynx in winter Holger Scmitt

Lynx Carlos Delgado

Amanita Muscaria: The Enchanted Mushroom Behind Christmas Lore

December 20, 2024

Widely recognised from cartoons to Christmas cards, the Amanita muscaria mushroom, with its iconic white-spotted red cap, has a surprisingly rich history rooted in European folklore.

Beyond its charming appearance, the history of the fly agaric, or fly amanita, is steeped in mystery and fairy tales, capturing the imagination of Europeans for centuries.

For generations, indigenous tribes such as the Scandinavian Sámi people have used this mushroom in shamanic rituals and ceremonies. After careful preparation, it is consumed to induce dreamlike states of consciousness, facilitating spiritual journeys believed to connect users with the spirits of the natural world and their ancestors.

In modern times, the Amanita muscaria has gained an intriguing association with the imagery and spirit of Christmas. While not often explicitly mentioned, scholars and folklorists have drawn parallels between its characteristics and various elements of holiday symbolism.

The winter solstice (December 21), which closely coincides with Christmas, was and remains a special time for tribal ceremonies. Shamans would gather the mushrooms, dry them by hanging them in tree branches or in socks placed near a fire—a practice believed to inspire the tradition of hanging stockings by the fireplace. Dressed in red and white garments, the shamans would distribute the mushrooms among villagers as offerings and blessings for the community. This is thought to have influenced the creation of the jolly, kind spirit of Santa Claus.

Moreover, these tundra cultures share deep and ancient connections with reindeer, which play both domestic roles and serve as a vital food source. Coupled with the induction of dreamlike states and the fact that reindeer also consume Amanita muscaria, it is easy to imagine how tales of flying reindeer might have taken root.

As a mycorrhizal fungus, Amanita muscaria forms a symbiotic relationship with the roots of trees such as birches, pines, and firs. The mushroom provides essential nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen, while the trees offer carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis.

The mushroom’s distinctive red-and-white caps emerge above ground during reproduction, releasing spores that contribute to soil fertility. Its presence in forests is a sign of a healthy ecosystem.

Amanita muscaria also serves as a cautionary symbol regarding the misconsumption of wild mushrooms. Improper preparation or consuming them raw can lead to symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, nausea, confusion, perspiration, and difficulty breathing. However, the mushroom is not lethal.

Today, Amanita muscaria continues to captivate scientists, artists, and enthusiasts alike. Mycologists study its unique properties, exploring both its ecological roles and its psychoactive compounds, such as muscimol and ibotenic acid. While toxic in large doses, these substances show potential for applications in medicine and neuroscience, sparking ongoing research.

As you celebrate this holiday season, take a moment to marvel at the wonders of nature. May your Christmas be as magical as the Amanita muscaria itself. Merry Christmas!

Amanita MuscariaDieze Oost

Amanita MuscariaMichael Hartwich

Minke Whales: Navigating Survival in a Changing Ocean

December 6, 2024

As one of the smallest and most abundant baleen (filter-feeding) whale species, minke whales (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) play a vital role in the marine ecosystems and the cultures of coastal communities in the Northern Hemisphere.

First documented by Danish naturalist and explorer Otto Friedrich Müller in 1776, minke whales primarily feed on small fish, plankton, and krill. As the second smallest baleen whale species, after the Antarctic pygmy right whale, they reach maturity at seven to eight years old and attain a maximum average body length of eight meters and a weight of seven tons. Typically, they live between 30 and 50 years, though some individuals have been recorded living up to 60 years.

Minke whales are distinguished by white bands on each flipper, and they have between 240 and 360 filter plates on each jaw, depending on their age. Their stomach is divided into four chambers. Like other baleen whales, their feeding habits contribute to the “whale pump,” a mechanism that cycles nutrients from the deep ocean to surface waters. This vital process supports the proliferation of phytoplankton, which plays a key role in global carbon capture.

Owing to their size, the deaths and sinking of baleen whales create “whale falls,” where their carcasses provide unique, nutrient-rich habitats for deep-sea organisms in otherwise almost barren environments.

Throughout history, whales, including minke whales, have held a special place in the folklore, art, and traditions of many coastal cultures. In regions like the Arctic and North Atlantic, Indigenous communities have relied on whales for sustenance, crafting tools and ceremonial objects from their bones and baleen.

The global population of minke whales is divided into two main species: the common minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) and the Antarctic minke whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis). These species are further subdivided into subpopulations based on geographic range. While the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists the common minke whale as being of “Least Concern,” the Antarctic minke whale is classified as “Near Threatened” due to pressures from climate change and human activity.

Historically, minke whales were not primary targets of commercial whaling due to their smaller size and lower yield of oil compared to larger species like blue or humpback whales. However, as larger whale populations were decimated by overexploitation during the 19th and early 20th centuries, commercial whalers shifted their focus to minkes. Intense whaling pressure in the mid-20th century caused significant population declines, particularly in the Southern Ocean.

Climate change has had profound effects on minke whales’ feeding and migration patterns, as their primary food sources, such as krill, are disrupted by warming oceans and shifting global distributions.

Noise pollution from shipping, military activities, and industrial development further threatens minke whales by interfering with their communication and echolocation, making it harder for them to navigate and locate food. Additionally, entanglement in fishing gear remains a significant cause of injury and mortality, particularly in heavily fished regions. Despite international regulations and public opposition, whaling for minke whales continues in countries like Norway, Japan, and Iceland.

International efforts have achieved some success in protecting minke whales, such as the International Whaling Commission’s (IWC) moratorium on commercial whaling (1986) and the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). These initiatives have helped stabilize populations in the Northern Hemisphere.

In Britain, organizations like the Hebridean Whale and Dolphin Trust (HWDT) and the Marine Conservation Society (MCS) monitor minke whale behavior, migration patterns, and population numbers while advocating for an expanded network of marine protected areas (MPAs). However, this task is challenging due to the whales’ wide-ranging migratory habits, which are increasingly affected by shifting food distributions and ongoing whaling activities in nearby Scandinavian nations.

Minke whales are far more than majestic miniature giants of the sea, they are vital to ocean health and serve as ambassadors for the conservation of other baleen whale species worldwide.

Minke Whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata)

Minke Whale on its back

Minke WhaleJared Towers

The Pine Martens Return: Rewilding Britain, One Woodland at a Time

October 25, 2024

Heartening news has emerged from Dartmoor, Devon, where 15 pine martens have been reintroduced to their ancient habitat after more than 150 years of absence.

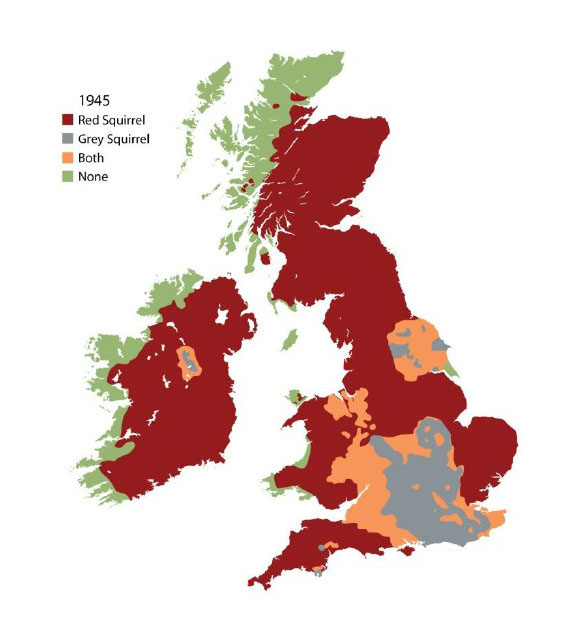

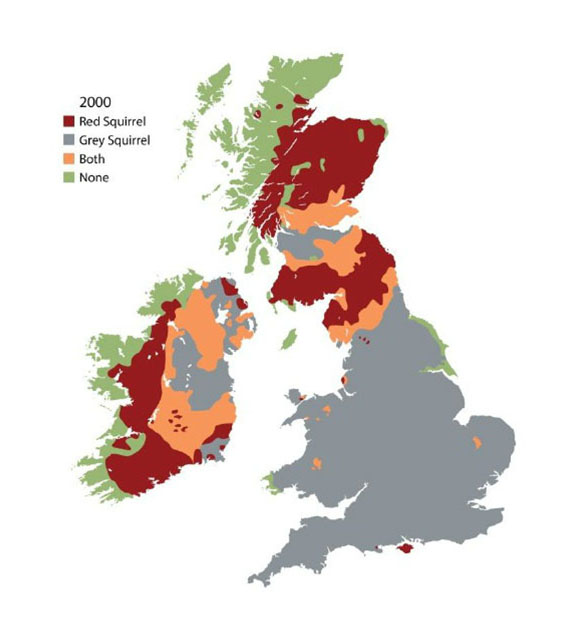

Led by Devon Wildlife Trust, the initiative is part of a nationwide effort to restore the endangered species, whose population is estimated at just 3,700. These elusive carnivores, expected to play a crucial role in controlling invasive grey squirrels, are poised to help revitalise ecosystems that have been degraded by the long absence of native predators.

As covered in one of our previous articles, pine martens (Martes martes) once thrived in Britain’s prehistoric Wildwood, a time when vast forests covered much of the main island of Great Britain. They were among the most abundant carnivores in Mesolithic Britain, contributing to the balance of ecosystems. However, centuries of deforestation and targeted persecution led to their near extinction.

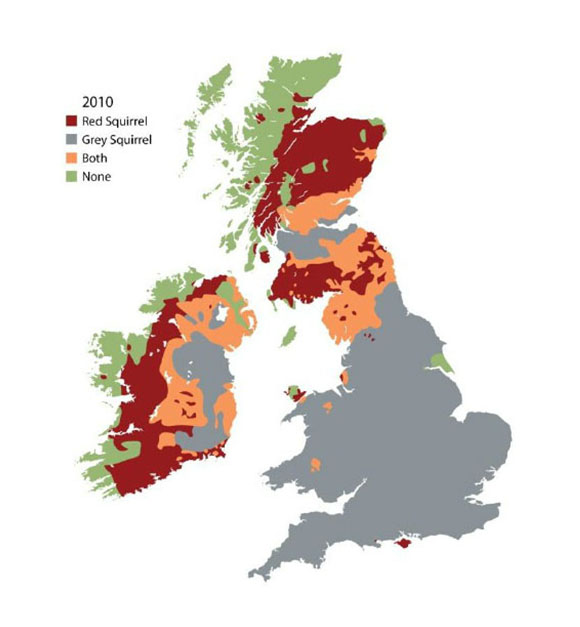

These agile, arboreal predators help control populations of rodents and other small mammals, acting as natural pest controllers. By preying on invasive grey squirrels, which were introduced to Britain in the 1870s, pine martens also help create conditions for the recovery of native red squirrels. In areas where pine martens have returned, studies show grey squirrel numbers decline, giving red squirrels a fighting chance to regain lost territories.

This 2024 reintroduction of 15 pine martens to Dartmoor is a milestone in the effort to restore this native species to its former range. The project is the culmination of six years of preparation. The animals, sourced from Scotland’s thriving pine marten population, were equipped with GPS and radio tags so they can be monitored and protected into the future.

Initial results from monitoring have been positive, with the pine martens avoiding human infrastructure and adapting well to their new environment. This release is the first step in a larger plan to establish a self-sustaining population in Devon, with future reintroductions planned for Exmoor further north.

While the Dartmoor reintroduction is making headlines in the southwest, Kent Wildlife Trust (KWT) is leading the charge in the southeast with its Wilder Kent initiative. Launched in 2019 and supported by a grant from Restore Our Planet, the project aims to restore 30% of Kent’s land and sea to wildlife, effectively doubling the county’s wild areas. Central to this plan is the reintroduction of species that have been extinct in the region, including pine martens, red squirrels, turtle doves, red-billed choughs, and beavers.

In both Dartmoor and Kent, the return of pine martens represents a broader movement towards rewilding and ecological restoration across Britain. These efforts are not only about saving a single species but about restoring the natural processes that sustain biodiversity and create resilient landscapes. With continued support, projects like these offer a hopeful vision for the future, where other endangered native species can begin to recover.

Pine Marten at the British Wildlife Centreby Surrey John

Pine Marten in Scotland

Red squirrels continue to make some ground in the battle against greys

October 4, 2024

We have previously reported on the plight of red squirrels and the sustained efforts of local groups to protect them. Now, promising updates have emerged from Scotland.

With significant reductions in invasive grey numbers in key regions, there are signs of optimism that red squirrels could soon regain territories where they had previously been driven out.

One of the most promising developments has taken place in Aberdeen, where the Saving Scotland’s Red Squirrels (SSRS) project, led by the Scottish Wildlife Trust, is approaching a breakthrough in its long-running initiative to eliminate greys from the city. Since the campaign began in 2009, more than 10,000 grey squirrels have been removed. Now it can be confirmed that sightings have dwindled to just 12 in 2024, suggesting the city is on the verge of being declared ‘grey-squirrel-free’.

Dr. Emma Sheehy, head of SSRS’s grey eradication initiative in northeast Scotland, confirmed that only three individual grey squirrels were detected at feeders out of more than 5,000 checks. “This is a result of long-term, consistent trapping,” she said. “Although it may seem counter-intuitive, this late stage of the removal phase is undoubtedly the biggest challenge the team will have faced to date.”

The remaining few greys are elusive and hidden among urban areas, making tracking and trapping significantly more difficult. However, Sheehy is hopeful that a concerted final push, combined with public support through sightings and reporting, could see Aberdeen become a secure red squirrel refuge “in the near future.”

We previously highlighted the remarkable yet often overlooked success story in Anglesey, Wales, which has become a shining example of red squirrel conservation. After being driven to near extinction in the 1990s, the island’s red population rebounded spectacularly, thanks to a systematic grey eradication program and targeted reintroductions. The number of reds now sits at around 700-800 individuals, a stark contrast to just a few dozen a little over two decades ago.

The Anglesey project serves as a model for other areas grappling with grey squirrel dominance. The central lesson of this success is that if greys can be removed completely, reds can thrive even in areas where they were once extinct. This model is being adapted in other red squirrel strongholds, including Brownsea Island and the Isle of Wight, where similar eradication efforts are ongoing.

Although the situation remains precarious for red squirrels, there are also signs that their decline is starting to stabilise. According to surveys in Scotland, reds have made gains in several locations along the Highland Boundary Fault Line, a crucial natural barrier that conservationists have been using to prevent further grey encroachment into red territories. Participants reported more sightings of reds than greys for the first time in years, indicating that suppression strategies are having an impact.

Local volunteer groups led by the Red Squirrel Survival Trust (RSST) also continue to fight back across northern England. Spokesman Mark Henderson in discussion on a recent episode of our podcast commented on volunteers saying “if it wasn’t for their work then the game would already be up, and the red squirrel would already be gone.”

Though promising stories are beginning to emerge it is still an uphill battle. Even in areas where reds have gained ground, grey squirrels are never far off, and a single outbreak of squirrelpox (carried by greys which are immune) could reverse years of progress. Conservationists remain cautious, emphasising that continued monitoring, public engagement, and consistent management will be essential to securing the red squirrel’s future.

Red Squirrel in the forestPeter Trimming

Duthie Park, Aberdeen.

From Silent Spring to Revival: The Recovery of Britain’s Otters

September 24, 2024

Along with countless other species, many of which we have covered in this article series, the European otter (Lutra lutra) suffered tremendously through the events of ‘Silent Spring’ – the phenomenon of mass die-outs of species following massive increases in chemical uses in agriculture across post-war Britain.

Through decades of determined conservation efforts, the otter has avoided extinction where its numbers fell by as much as 90% through the mid-20th century. In eastern England it was entirely wiped out.

In the 1970s it was only found in 6% of survey sites in England and 17% in Wales. This decline came largely at the hands of organochlorine pesticides, mostly dieldrin and aldrin, which penetrated water systems, entered the food chain, and killed otters through the consumption of poisoned fish. Their numbers were further decimated through illegal hunting in pursuit of their prized hides and rapidly increasing habitat destruction.

Many harmful pesticides were banned towards the end of the decade reducing pollution in freshwater systems. To fight poaching the Wildlife and Countryside Act of 1981 was then passed. Following these landmark first steps, habitat restoration initiatives commenced focusing on improving the water quality across ecosystems, restoring riverbanks and constructing otter ‘holts’ (dens).

So successful were these efforts that by the early 1990s otters were found across 36% of sites. Reintroductions also brought them to areas they were previously extinct such as East Anglia and the Midlands. By 2010, this number had further increased to 59% of sites and 96% by 2018. This remarkable recovery accounts for a near complete restoration of Britain’s otter population in half of a century.

Today, otters are present in every county in England, Wales, and Scotland, with Scotland and Wales serving as population strongholds. Their recovery has been most rapid in northern and western regions, while southern England has seen slower progress.

As apex predators, otters play a critical role in maintaining the health of freshwater ecosystems. Their diet consists primarily of fish, but they also eat amphibians, crustaceans, and small mammals. They are also considered indicator species and their recovery signals wider improvements in river quality, which benefits other species such as water voles, kingfishers, and dragonflies. Additionally, otters contribute to nutrient cycling, transferring nutrients between aquatic and terrestrial environments, which boosts productivity along riverbanks.

Otters have long held a special place in British culture, symbolising playfulness, intelligence, and the wild beauty of the countryside. In folklore, otters were often associated with magic and mystery, believed to possess shape-shifting abilities or act as spirit guides in Scottish and Irish mythology. In literature, otters have been immortalised in works such as Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1908) and Henry Williamson’s Tarka the Otter (1927), both of which helped shape public affection for these animals.

While otters have made an impressive recovery, they still face threats. Road traffic accidents are now one of the leading causes of otter deaths, as they often travel between waterways to find food or mates. Conservationists are currently working in tandem with government ministries to find ways to improve infrastructure to accommodate otters and other vulnerable species. This is important not only in the service of finding food, but natural migration serves to prevent the isolation of populations which bring genetic threats associated with inbreeding.

Pollution from agricultural runoff, especially pesticides and fertilisers, continues to pose a risk to river health. The impacts of climate change, such as rising water temperatures and altered river flows, could also affect otters’ food sources and habitats in the coming decades, particularly in southern England where populations are still recovering.

In conclusion, the resurgence of otters in the UK is a remarkable conservation success story. Their recovery not only benefits biodiversity but also reflects wider improvements in the nation’s freshwater ecosystems. Otters, once nearly wiped out, are now thriving and remain a beloved part of Britain’s natural and cultural heritage.

Otter in FranceBernard Landgraf

Otters playing

Otter eating a fish in Hannover Michael Gabler

The Soaring Return of the Red Kite

September 4, 2024

A welcome sight for motorists leaving London for the Home Counties, red kites (Milvus milvus) with their striking reddish-brown plumage and distinctive forked tails, are often seen gracefully gliding through the skies. These elegant raptors, known for their iconic hovering over farmers’ fields as they scan for small prey, embody a remarkable conservation success story, having made a dramatic comeback from the brink.

Although they are predators, red kites primarily feed on carrion, playing a crucial role as part of nature’s ‘cleanup crew.’ By removing dead animals from the landscape, they help prevent the spread of disease in turn promoting healthier ecosystems for other species. This scavenging process not only reduces the risk of pathogens spreading but also recycles vital nutrients back into the soil, enriching the environment.

The red kite’s diet includes small mammals, birds, and insects. While they prefer broadleaf deciduous woodlands, their varied diet has allowed them to adapt to a range of environments, including expanding urban areas where they can now often be seen in suburban neighbourhoods.

Like many of the animals we have covered, red kites serve as an indicator species, with their presence signaling a healthy environment. As apex predators, their population is regulated by the availability of prey species, rather than the other way around, as is often believed. This dynamic indicates that the ecosystems they inhabit can support a robust and diverse range of wildlife, reflecting the overall health and balance of the food chains they are part of.

In medieval times, red kites were a common sight in towns and cities, where they were revered and celebrated for their vital role in keeping the streets clean by scavenging waste. However, by the 19th century, they faced the tragic fate shared by many other important and magnificent native creatures: mass persecution as vermin by hunters and landowners. This relentless hunting led to a catastrophic decline in their populations, pushing them to the brink of extinction across the British Isles, with only a few breeding pairs surviving in Wales.

Efforts to reverse this tragic decline began in the late 20th century with the launch of dedicated conservation initiatives. During the 1980s and 1990s, breeding pairs were reintroduced into areas from which they had been eradicated, including the Chilterns, the Black Isle in Scotland, and Harewood in Yorkshire. Thanks to these efforts, the red kite population has rebounded significantly, with an estimated 5,000 breeding pairs now thriving across Britain.

Today, as you travel across the country, the sight of red kites soaring high serves as a powerful reminder of nature’s resilience and the positive impact of concerted conservation efforts. These graceful birds are often highlighted in education and public advocacy as a testament to how small, dedicated groups can successfully bring a species back from nearly disappearing entirely.

The dramatic recovery of the red kite, alongside other species in recent decades, offers a beacon of hope in an era often overshadowed by dire news about climate change and habitat destruction. Time and again, dedicated organisations and local groups have demonstrated that it is possible to reverse environmental decline through focused efforts on habitat preservation, restoration, and informed species reintroductions. While there is still much work to be done, the sight of red kites soaring and hovering over England’s fields is a heartening reminder that positive change remains within our reach.

Young individual. Cookham

Three nesting Red Kites

Restoring One of Britain’s Most Endangered Bat Species

August 23, 2024

Reflecting the broader decline facing much of the country’s wildlife, Bechstein’s bat (Myotis bechsteinii) has been confined to southern England and parts of southeastern Wales following decades of intense agricultural management practices and devastation to ancient woodlands, habitat outside of which they are rarely found.

Like many bat species, it is elusive, making population estimates challenging. However, conservationists now estimate its numbers to be in the low tens of thousands, a sharp decline from previous decades.

These bats thrive in “old-growth” environments, favouring woodlands with a dense understory and abundant dead trees and branches for roosting, hibernating and breeding. They are highly dependent on the ecological activities of other species, often roosting in tree holes created by woodpeckers or behind loose, peeling bark created by mammals such as squirrels.

Being so highly adapted to its habitat has been a mixed blessing for conservationists. It allows for management efforts to be more tailored to particular needs while also leaving it vulnerable to slight changes in woodland conditions. Since these bats depend on mature forests, restoring suitable conditions for population growth can be a lengthy process, often requiring many years for the forest to regrow and support expanding populations.

Moreover, unlike other bat species that have adapted to human expansion by often taking refuge in man-made structures, Bechstein’s bats do not and therefore remain closely tied to the fate of ancient woodlands making the long term preservation of these ecosystems that much more crucial.

Local wildlife groups have taken on the challenge with monitoring and protective measures in recent years by organisations such as the Vincent Wildlife Trust (VWT), the Bat Conservation Trust.

A project worthy of highlighting has been underway at Bracketts Coppice Nature Reserve in Dorset, a site that has become a launchpad for the Bechstein’s bat’s recovery. Managed by the Dorset Wildlife Trust in partnership with the VWT, this reserve covers 46 hectares of ancient woodland. It is a designated Special Area of Conservation (SAC) and a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), primarily due to its large population of Bechstein’s bats.

Following the installation of 30 bat boxes in 1998, the population has continued to grow now providing over 25 years of data. Conservationists have focused on expanding and improving a dense understory of habitat growth using the ancient method of coppicing to allow sunlight to reach the forest floor.

In conclusion another species headed toward the brink of disappearing now has a tentative but encouraging future owing to the determined actions of small dedicated groups. However, to really make a difference to secure its future across a greater range much more work is needed. But for now things are looking brighter for the Bechstein’s bat.

Myotis bechsteinii hunting moths

Bechstein`s bat resting in a cave

Saving the Sand Lizard

July 26, 2024

Found only among certain southern patches of heathland and coastal dunes, or areas with sandy soil such as Wales, Essex, Dorset and Hampshire, the vibrant green sand lizard (Lacerta agilis) is one of Britain’s rarest reptiles.

As with so many other species across the country, the sand lizard once enjoyed widespread habitats and a healthy environment. It requires the open, sunny conditions essential for the species’ thermoregulation and breeding. However, the dramatic urban development and intensification of agricultural chemical use of the 20th Century left the small reptile’s population in a sorry state. Exact numbers are difficult to ascertain due to its elusive character and the variability in monitoring practices.

In the nineties conservationists efforts began. These included captive breeding, habitat restoration and reintroductions alongside advocacy campaigns to engage and inspire the public. Sandy environments have been recreated along the Thames Estuary and animal grazing have been used to improve suitable heathlands. In Surrey and Dorset, topsoil was removed to expose bare sand perfect for nesting. Work is also underway to reconnect fragmented habitats through wildlife corridors to improve genetic diversity and reduce the risks from inbreeding.

Sand lizards serve as both predators and prey. Utilizing their speed and agility, they primarily feed on invertebrates, while also being a food source for birds of prey and mammals.

As indicator species they are a welcome sight. Their presence means the ecosystem is working well for other creatures and drives to conserve and increase their numbers serve wider biodiversity goals.

Amphibian and Reptile Conservation (ARC) has been at the forefront of captive breeding programs, successfully propagating sand lizard numbers in carefully monitored environments. These efforts have led to the release of hundreds of individuals into the wild, significantly aiding in the species’ recovery.

These reintroduction programs are carefully monitored to ensure the lizards adapt well to their new environments and begin breeding successfully. Sites are chosen based on habitat suitability, with ongoing management to maintain optimal conditions. The success of these programs is evidenced by the establishment of new, self-sustaining sand lizard populations in areas where they had previously disappeared.

Having acknowledged the wider plight of countless British species, the government has also taken positive steps by introducing policies and regulations to encourage local authorities and developers to consider wildlife in planning.

Despite these positive trends there is still a long way to go for vulnerable and rare species such as sand lizards. However, collaborative efforts offer hope.

By continuing to manage and expand appropriate sand and heath habitats, nurturing their populations through captive breeding and pressuring governments to introduce protective legislation the long term prospects of sand lizards begin to look brighter.

Male Sand Lizard

Male and Female Together

Common kestrel with caught sand lizard Jakub Halun

A Tribute to London Wildflowers

July 19, 2024

The United Nations defines a forest as any area where the tree canopy covers more than 10% of a land expanse larger than half a hectare. By this standard, London, with 21% of its vast 150,000 hectares covered by towering greenery, can be considered a forest in its own right. With over eight million trees, there are almost as many as there are people.

Despite being so interwoven by rail, inexhaustible brick, and endless tarmac, London is recognised as the world’s largest urban forest. Its trees span streets, parks, ancient churchyards, and woodlands, surpassing Berlin, which ranks second with a 14% canopy cover.

Tucked beneath this leafy celebration are hosts of magnificent wildflowers: primrose, bluebells, campion, knapweed. Urban meadows blossom through the wetlands of Walthamstow and Barnes, Hampstead Heath, Putney Heath, Ruislip. They thrive in the gardens of Dulwich, Regent’s Park, Bushy Park. The Big Smoke has grown into The Great Woods!

The iconic Common Knapweed (Centaurea nigra) alone invites over a hundred species of insect. Red Campion (Silene dioica), championed by folklore as the guardian of honey stores, is a chief biodiversity indicator. The Oxeye Daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare), symbol of new beginnings, is a pioneer species colonising tougher terrains for other flowers to follow.

Wildflowers have supported pollinators to unlock the exponential green growth we see across our city. Though many of these species such as bees, butterflies, and hoverflies have experienced devastating declines, these blooms provide desperately needed sanctuary to these crucial creatures.

Plants such as Clover (Trifolium spp.), extremely common across grassy areas, fix atmospheric nitrogen into the soil, enriching it and promoting the growth of other plant species.

The UK’s Bumblebee Conservation Trust highlights the importance of plants like the Kidney Vetch (Anthyllis vulneraria), which supports the endangered Small Blue butterfly. Similarly, the early spring blooms of the Primrose (Primula vulgaris) provide a vital nectar source for bees emerging from hibernation.

These flowers contribute significantly to the overall environmental health of the urban environment. Their deep root systems support soil stabilisation, reduce erosion, and improve natural water infiltration and flow. This is beneficial in urban areas where soil compaction and runoff can lead to flooding. This is particularly evident in heavy rains when drainage systems often overflow into the streets.

Owing to their beauty, public spaces adorned with wildflowers evoke strong feelings of harmonious pleasure where otherwise oppressive noise and toxic pollution sadden the soul. It is not surprising that green spaces are shown to improve mental health, reduce stress, and foster a sense of community and respect for one’s surroundings. A local sense of beauty even reduces littering, graffiti, and petty crime. Wildflower meadows provide a tranquil retreat from the usual stress of urban living. These retreats not only enhance biodiversity but also bring nature closer to London’s residents, offering opportunities for education and improving urban resilience to climate change.

To foster the thriving of wildflowers in public spaces across Britain is an endeavour with many blessings. London is a miracle. From enhancing biodiversity and supporting pollinators to improving environmental health and fostering community well-being, its forests are indispensable. Our city exemplifies how even densely populated cities can integrate and benefit from these natural treasures, reinforcing the timeless connection between humans and the natural world. And by valuing and protecting wildflowers, we not only safeguard our environment but also enrich our lives and the legacy we leave for future Londoners.

Small Heath Butterfly on Common Knapweed ( Centauria nigra ) C J Sharp 2016

Red Campion ( Silene dioca ) P J Fischer 2016

Oxeye Daisy { Leucanthemum vulgare ) D Ramsey 2007

The Tentative Return of the Scottish Wildcat

July 2, 2024

Given the exciting recent news that Scottish wildcats have started breeding in the wild, let’s explore the overall importance of Felis silvestris grampia in their natural habitat.

We have previously covered wildcats more generally in our Wilding Profiles, but now let us look a little deeper.

The Scottish wildcat is one of the most iconic and endangered mammal species in the United Kingdom. Known for its elusive nature and resemblance to many domesticated cats, this wild relative favours the remote, rugged heathlands and woodlands. Here, it thrives, hunting small mammals through dense thickets.

These vegetation-covered habitats provide protection, particularly for kittens, against predatory birds such as sparrowhawks and golden eagles, as well as the bluster and dreich Scottish weather. Historically, these cats hunted across the country, but human-led habitat loss and development have restricted their numbers to the Highlands.

Scottish wildcats are larger and more robust than their house-dwelling counterparts. They have much bushier tails with distinctive black rings and dark tips. Generally, their heads are larger, and due to their environment, they sport much thicker fur.

Their diet primarily consists of small mammals, particularly rabbits and rodents. They are also known to hunt small birds and pluck amphibians from the water. As with most cats, wildcats are solitary hunters, preferring to stalk during the night and twilight hours. Using their keen senses, they choose stealth over pursuit, and the pounce over the chase.

They reproduce once a year during spring, after the mating season in the winter months. After around 65 days of pregnancy, they give birth to a litter of between two and six kittens in the seclusion and safety of their deep forest dens. Following six to eight weeks of milk, the kittens are weaned but remain at their mother’s side until around six months of age, reaching full sexual maturity at one year.

Preferring lives of solitude over living in groups, their territories can vary according to the availability of prey and quality of habitats. Males generally have larger territories that overlap with those of several females, while females have smaller, more exclusive territories. Territorial boundaries are marked using scent glands located on their face and paws, as well as through urine spraying and fecal deposits.

The current population of Scottish wildcats is believed to be between 100 and 300 individuals. However, with this welcome recent news, high levels of public advocacy, and conservation support, let’s hope these numbers continue to increase and a once-widespread iconic species of the British Isles can thrive.

Mother with kitten. British Wildlife Centre, Surrey.

Released cat on camera. Saving Wildcats.PA Wire.

Britain’s adders: the forgotten serpent?

June 5, 2024

Britain’s only venomous snake, the adder (Vipera berus), is experiencing a significant decline. Once widespread throughout the country, these elusive snakes have been silently enduring a devastating population collapse for decades.

A recent survey indicates the population has suffered up to a 90% decrease, reduced to the dwindling pockets of their heathland, moorland, and forest edge habitats. Technically, they can be spotted across all regions of the country, with numbers now believed to rest at approximately 100,000. Though this leaves them out of danger of extinction for now, the trend is worrying, especially given their status as an indicator species: a measure of overall biodiversity health.

All has not gone completely unnoticed. The Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 made it illegal to kill, injure, harm, or sell adders, and they have been classified as a Priority Species under the UK Biodiversity Action Plan. However, generally in wider society, the plight of the adder falls outside mainstream conversation.

Several factors have contributed to the adder’s sharp decline. Habitat loss and fragmentation through human development are primary culprits. Farm expansion, urban development, and infrastructure projects have encroached upon their natural habitats, leaving them with increasingly isolated and degraded environments, harming their genetic diversity and access to food sources.

Adders rely on specific temperature ranges to regulate their body heat, and changes in weather patterns can disrupt their hibernation cycles (October to March) and reproductive success. This has left them particularly vulnerable to climate change. Additionally, human persecution, driven by fear and misunderstanding of these snakes, continues to impact their chances for recovery. Adders are sadly often killed on sight, despite being generally non-aggressive and posing little threat to humans when left undisturbed.

Like other mid-level predators, adders help control populations of small mammals, such as rodents, which serve as their primary prey. They also provide crucial prey for larger predators, particularly birds of prey and mammals such as foxes.

Adders appear in various British folklore and myths, often associated with danger and mystery due to their venomous nature. They were sometimes believed to be creatures of ill omen or associated with witches and dark magic. However, they were also respected and feared, symbolising the wild and untamed aspects of nature. In Shakespeare’s works, snakes are often used to depict betrayal and hidden dangers.

The adder’s image is also prevalent in local traditions and stories, particularly in rural areas. For many, encountering an adder in the wild remains a memorable and profound experience, connecting people to the natural world and its mysteries.

It is for these reasons that more must be done to save the adder.

Educational campaigns aimed at dispelling myths and reducing the fear surrounding these snakes would promote a more positive perception. Community involvement through workshops, public talks, and the distribution of educational materials. By fostering a better understanding and appreciation of adders, these initiatives help build support for their conservation.

Mitigating specific threats to adders is a key aspect of conservation efforts. Given the devastating levels of defragmentation their populations suffer due to infrastructure networks, road mortality is a significant issue, and measures such as wildlife crossings and road signage reduce the risk of roadkill.

Several organisations are at the forefront of adder conservation, particularly The Amphibian and Reptile Conservation (ARC) Trust, which conducts research, habitat management, and public outreach.

By addressing the threats adders face, many other species and habitats will benefit, not just Britain’s only native venomous snake. Through a combination of research, public engagement, and policy measures, the decline of this remarkable species can be reversed for future generations.

Common Adder.

By Benny Trap.

Adult female. Loch Shin, Scotland 2008.

Two colour variations. 2008.

The incredible comeback of Britain’s Barn Owls

May 30, 2024

With its charming heart-shaped face and graceful plumage, the barn owl (Tyto alba)’s haunting nocturnal cry can be heard through the British night as it preys upon small mammals such as mice, shrews and voles.

As the iconic apex predator maintains control over these small mammal populations, they have become farmers’ friends as natural pest controllers. Centuries of good-will have given rise to barn owls being a most welcome sight and praised through folklore and art.

A single barn owl family (usually three- twelve individuals) can consume thousands of rodents a year not only providing significant economic benefits to farmers, but improving habitats such as grasslands, marshes and fields.

An overpopulation of rodents brings a plethora of problems for surrounding plants and beasts. They feast on small birds and their eggs; seedlings which inhibit the proliferation of flora; and act as conduits of diseases. This hinders agricultural production and increases health risks to animals, plants and humans.

The health of barn owl populations therefore reflects the broader health of their surrounding ecosystems, as they are sensitive to changes in land use and environmental quality. Conservation efforts aimed at protecting barn owls often result in broader environmental benefits, such as the preservation of hedgerows and field margins that support a variety of other wildlife species.

Barn owls hold a prominent place in the cultural fabric of the British Isles. Their ethereal appearance and nocturnal habits have inspired numerous myths, legends, and superstitions. Among the celts, owls were considered to possess wisdom and were believed to be guardians of the underworld, associated with the afterlife and transformation.

In English folklore, the barn owl was often seen as a harbinger of change, both good and ill. Their eerie calls in the night led to their association with ghosts and spirits. However, they were also seen as symbols of protection, believed to keep away evil spirits from farms and villages.

In his plays William Shakespeare often referenced the “obscure bird” and their likeness has appeared in countless artforms. Famously in more recent history, J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series further cemented the barn owl’s place in popular culture with the character Hedwig.

Historically, barn owls have been closely associated with pre-modern human settlements and agricultural livelihoods. Their name itself derives from their tendency to nest in barns, churches, and other man-made typically rural structures.